2.6 British Radicals: The Crystal Palace, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and Aestheticism

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Victorian England saw huge social and economic change from the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution. Much like how Realism sought to reckon with these changes with social grounding, others sought answers in the past. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists that wanted to combat an over academic art world, looked to literary and religious subject matter and the emotional directness of medieval and early renaissance art.

Smarthistory: Intro to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

A classic example of PRB painting is John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, a subject drawn from Shakespeare and painted with extraordinarily vibrant colors and exacting detail. The story of Millais’s completion of this painting is a testament to the dedication of the PRB.

Optional: Smarthistory: Millais, Ophelia

Dante Gabriel Rosetti was both a poet and painter and painted many portraits of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal. In one of the most well-known, completed shortly after her tragic death, Rosetti depicts her as Beatrice, the muse of Virgil in Dante’s Inferno.

Optional Smarthistory: Rosetti, Beata Beatrix

What makes these works by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood “modern,” even though they reference the literary past? How do their concepts about art, the artist, or society relate to modern art and the other movements we have been studying?

PRB painters did not only paint literary subject matter, however, and often used the same visual style to connect to the modern city. Ford Madox Brown used a monumental composition to depict toil and class divisions in Work.

What connections and differences do you see between this approach and that of Courbet?

The Crystal Palace

The hyper-industrialized Victorian world the PRB was responding to is perhaps best embodied in the Crystal Palace, a technological marvel of iron and glass that displayed the latest products and technologies in the first international exposition. This building is not only significant in architectural history, but also in the history of nineteenth century visual and consumer culture.

Aestheticism

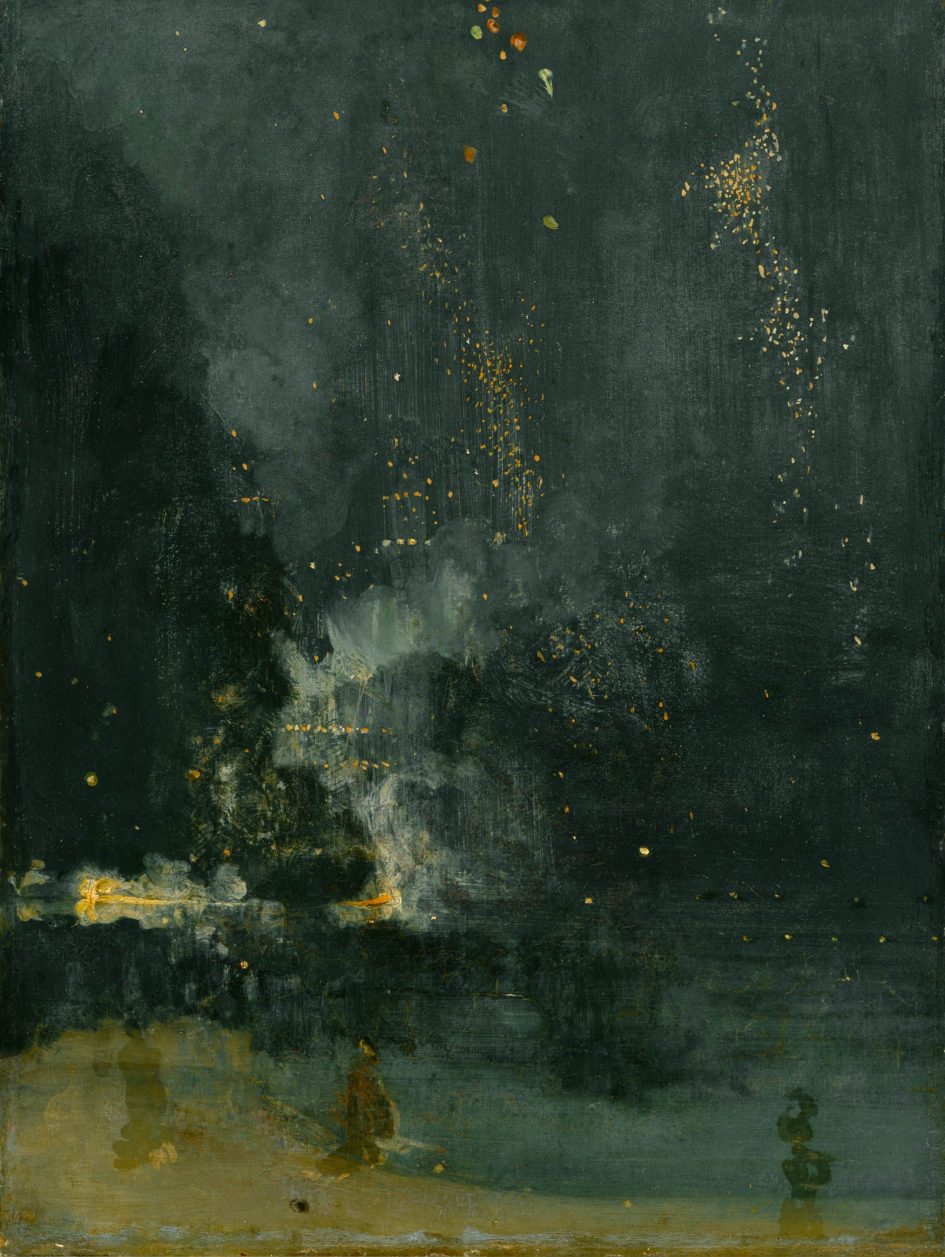

James Abbot McNeill Whistler, an American expat living abroad, made quite a stir in the London art world when he started showing paintings that were more interested in formal decisions than subject matter. Whistler’s titles, often using musical terms, foregrounded his paintings’ use of color, suggesting that the aesthetics of a work of art should trump any subject matter. So controversial where his ideas that the critic John Ruskin claimed the artist basically threw paint into the public’s face, causing Whistler to sue prompting one of the art world’s most notorious legal cases (and your primary source reading for today).

Smarthistory: Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold

Primary Source: Whistler Trial

What is at stake in this debate? What is the nature of each side’s definition of “art” or of the artist’s labor? How do these debates affect the later development of modern art?

Summary Questions

In what ways were the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Whistler “avant-garde”?

How did artists take on the mantle of shock and challenging the status quo in very different ways?

Although they explicitly reference an earlier time in their name and subject matter, were the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood modern?

What major consequences does Whistler’s trial have for our idea of art?

Outline for Class Notes: